|

By Bernie Bierman - Class of Spring 1951

(As seen on Facebook, Graduates of the High School of Music and Art in New York City, August 31, 2015)

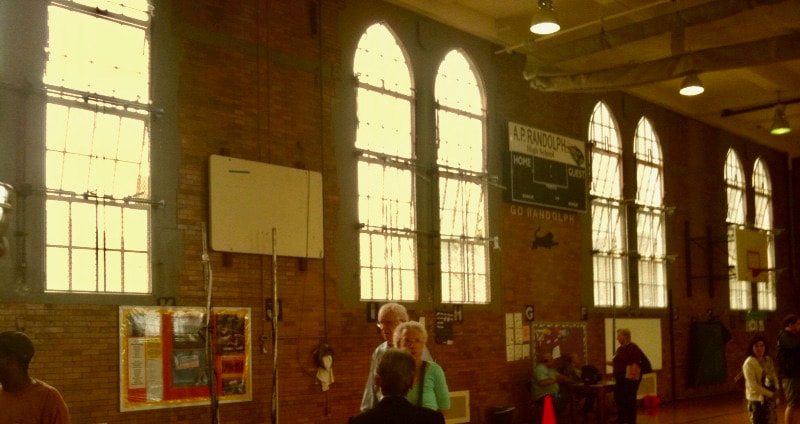

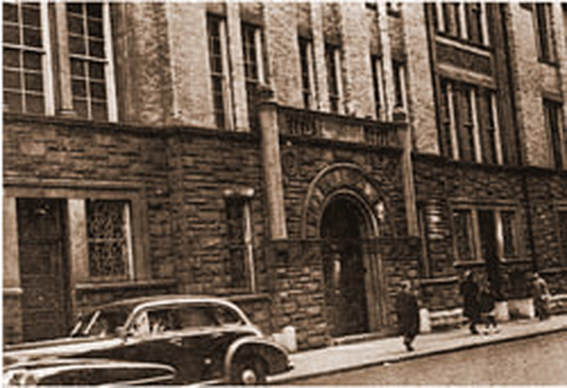

On June 9, 2001, some 60 members of the June 1951 graduating class went to St. Nicholas Heights to see the old Castle-on-the-Hill. The visit was part of a 3-day celebration of their class’ 50th graduation anniversary. The name in Gothic letters “High School of Music and Art” over the main entrance was of course absent. It had been removed about 17 years previously. But the Gothic-style building was very much there, as majestic as it was when those 60 members of the Class of June 1951 left it for the last time all those many years before.

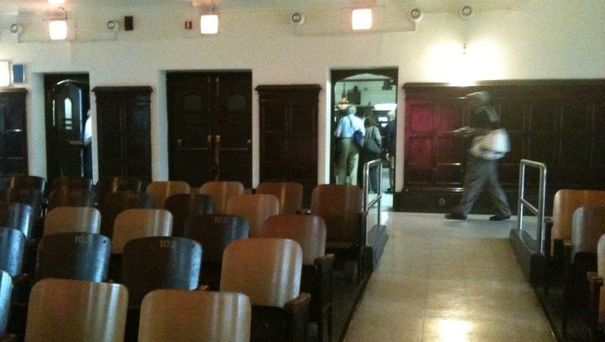

When we entered the lobby, every single one of us felt as if we had entered a time machine. The dark wood-paneled lobby had barely changed. It was the same lobby that we saw every day for four years. If there was any change, it was the absence of the bust of Maestro Arturo Toscanini, who used to welcome both teachers, students and visitors. He too, like the Gothic letters over the main entrance, had been removed. And that very same time machine effect continued when we entered the auditorium. Here too, nothing had changed since June 26, 1951, or at least nothing that was immediately visible to the eye.

However, physical change was easily discernible elsewhere in the old castle. The music rooms, the art rooms were gone. The massive orchestra room had been partitioned into several chemistry rooms. Lockers lined the hallways. Classroom furniture had been modernized. Other physical signs of modernity were everywhere, including a sign in the state-of-the-art gym that directed students to the place where they could obtain condoms. But all of this was to be expected, for after all, 50 years had elapsed. The old castle-on-the-hill was no longer the High School of Music & Art. It was now the A. Phillip Randolph High School. I could not help but think of the words of Gertrude Stein, “You can’t go back there anymore because there isn’t there anymore”.

* * * * *

Structural changes are certainly not the sole markers of history. They are not even the principal markers. Rather, the principal markers of history are evolutionary changes. The evolutionary changes that were wrought over the years at the High School of Music & Art were to be sure not self-created or self-generated. On the contrary, those evolutionary changes came about because of external forces.

The High School of Music & Art of the first decade-and-a-fifth (1937-49) was not the High School of Music & Art of the second decade (1950-60), for the simple reason that the environment in which it existed - New York City - was not the same in the former-mentioned decade as it was in the latter-mentioned decade. And on an even grander scale, the America of the 1940’s was not the America of the 1950’s. The evolutionary changes that occurred in the 1960’s, the 1970’s and the 1980’s were even more pronounced and powerful.

In addressing some of the changes that occurred in the school over its nearly half-century history, it might be instructive to use the subjects of art and music as points of reference: I remember in the late Spring of 1991 walking the hallways of the then-new LaGuardia High School with my classmates, looking at the various works of art that lined the walls or otherwise placed within the hallways of the school. There were soft smiles on the faces of many of the art majors, indicative of their pleasure at seeing the boundaries of art having been so broadly extended. I distinctly recall the words of one of my art major classmates who when looking at a piece of very modern sculpture done by a LaGuardia student, remarked “When we were kids, that would have been rejected even by the Museum of Modern Art”. What was defined, generally speaking, as art in 1950 would cause an M&A art major of 1970 either to bellow in horror or to “LOL”. By way of one small example, in 1950 photography was not considered an art form. In fact, any suggestion that photography was an art form would have been met by skepticism at best and ridicule at worst. Photography was viewed as the product of a mechanical device. You clicked a shutter and you got a picture. The idea of teaching photography as an art form was unheard of. But aside from just photography, the boundaries of art were still relatively restricted.

On the music side, the reins were just as tight and the boundaries just as restrictive. The expression “classical music” was often replaced by the term “serious music”, which clearly implied that musical forms other than “classical” were not serious. Instruments such as the accordion and the saxophone carried the adjective “illegitimate”. In 1950, there were musical instruments that were considered “female” instruments or “male” instruments. Girls played the harp. Boys did not. Boys played the trumpet and trombone. Girls did not. A “serious” musician did not play “that other kind of so-called music”. Jascha Heifetz, the world famous violinist and arguably the best in his field, was writing popular songs using a pseudonym; if such heresy had been exposed, tarring and feathering would have surely followed. The great conductor, Leopold Stokowski appeared at the school one day in 1950. It was as if God had entered the building. Would have Stephane Grappelli received the same welcome? A gospel chorus at Music & Art in 1950? “Have you taken leave of your senses?” would have been the response to such a concept, such a suggestion. A jazz ensemble? Not likely. Why George Gershwin, Cole Porter and Irving Berlin were viewed as below “acceptable” standards of music. An M&A student of the 1970’s or 1980’s would find such attitudes, such beliefs unbelievable, and therein lies some of the evidence of the enormous internal changes that the school experienced from one decade to another.

By the late 1950’s some of those barriers described started to crack, and by the 1960’s many had already fallen. As the 1970’s dawned. those barriers were crumbled ruins, curious relics of a past. (In Part 3, I’ll examine the core of the school and the effect of the great demographic changes of the 1960’s, 1970’s and 1980’s.)

Note: Instead of Part 3 (which is unavailable), the next story from Bernie Bierman will be Excerpt from "Confessions of a Faker."

0 Comments

By Bernie Bierman - Class of Spring 1951 (As seen on Facebook, Graduates of the High School of Music and Art in New York City, August 27, 2015) As is well-known to all of you, the High School of Music & Art was established in 1937 through the initiative of Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia. At the time of its establishment, it was one of the so-called “special” high schools of New York City, the others being Bronx High School of Science, Brooklyn Technical High School and Stuyvesant High School. All four schools required the passing of an entrance examination plus a higher-than-average elementary school or junior high school academic record. Music & Art was different from its three sister “special” high schools because it provided specialized education in music and the fine arts. However, it was very much like its three sister “special” high schools because of its emphasis on academics and academic achievement. Music & Art was considered and was called an “academic high school”, to differentiate it from the institutions called “vocational high schools”. It is noteworthy that the diploma issued to M&A graduates read, “Academic Diploma with (Music)(Art) Major”. No other New York City high school of the time issued a diploma with such language.

During my four years at M&A (1947-51), there was always an air of condescension when speaking about PA. I recall the phrase, “English for Idiots” as an expression of mockery about PA’s academic standards. Dance, which was an important and integral part of PA’s curriculum and which did not exist at all at M&A during my tenure, was at least a decade away from achieving the recognition and prestige that the art form has today. In 1961, the two high schools were merged. While it was a legal and administrative merger, it was in reality a merger on paper only. The old jealousies and condescension did not evaporate overnight. According to various historical accounts, there was resistance to this merger from various quarters. In fact, some accounts suggest that the merger was driven more by budgetary exigencies than anything else. Which account is more accurate is something we may never learn. However, notwithstanding paper merger, talk of actual physical merge began in the mid-1960’s and intensified in the 1970’s, an intensification that included the appointment of a single Principal for both schools (now sometimes called “campuses”), culminating in 1985 with the physical merger of both schools at their new home near Lincoln Center in Manhattan, appropriately named for the man who inspired the founding of the High School of Music & Art, Fiorello LaGuardia. With the opening of the new LaGuardia High School for Music & Art and the Performing Arts, the old High School of Music & Art, which existed for some 49 years in an imposing Gothic-style building on St. Nicholas Heights, and through which some 115,000-125,000 students passed, was no more. To paraphrase Ben Hecht, “Look for it only in the history books, for it is a place that is now but a memory”. And the same can be said of the High School of Performing Arts. (To be continued if interest warrants.) |

Your TIMEOpinions and commentary from the alumni. ArchivesCategories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed